The Neighbourhood That Rewrote Medellín

Cities spend billions trying to “activate” public space. Comuna 13 did it with brick, paint, music, and a set of escalators clawing up a mountainside. Walking into it feels like stumbling into a city built on improvisation—walls turned to canvases, staircases to storefronts, every corner buzzing with kids, vendors, and beats spilling from balconies.

I’ve never seen a shopping mall so alive, yet this wasn’t a mall. This was a hillside once written off by the city, now vibrating with art, commerce, children darting between murals, and the hum of escalators ferrying people up steep slopes. Malls dream of activation like this. Developers sketch endless diagrams about “community engagement.”

But to feel the present, you have to know the past. Not long ago, Comuna 13 was shorthand for violence—the hillside where Medellín’s cartel wars and paramilitary clashes left scars both physical and invisible. In the early 2000s, government forces launched operations here, raids that tried to wrestle control but often deepened the trauma. For decades, this was a neighbourhood defined by absence: absence of infrastructure, absence of safety, absence of opportunity.

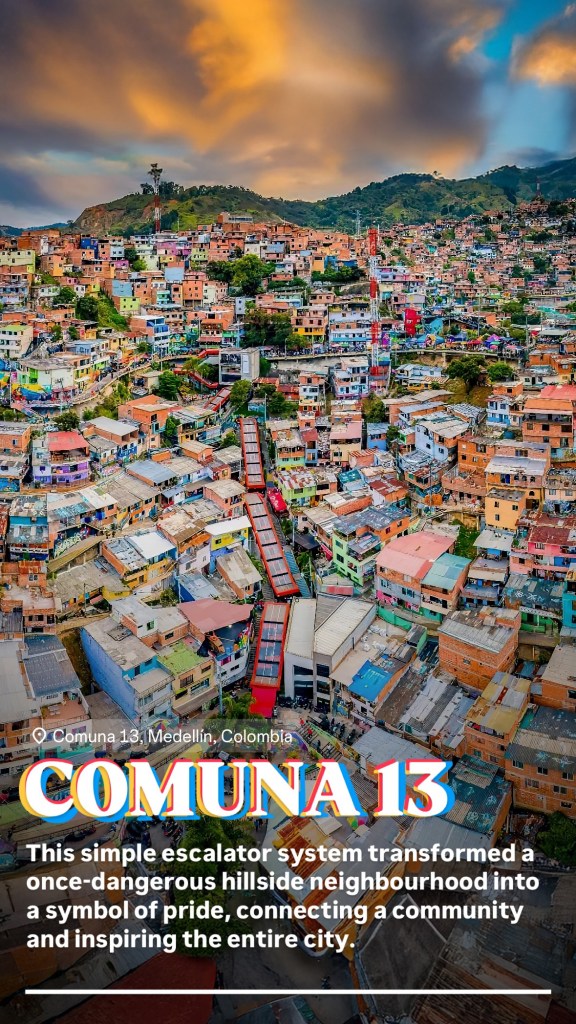

The turning point wasn’t just state action but state investment. Public escalators were built to climb the impossible slope—suddenly the city above and below connected. Then came cable cars linking Comuna 13 to Medellín’s transit spine, pulling the hillside into the flow of the metropolis. Infrastructure didn’t erase history, but it carved out possibility. Murals spread across walls like counterweights to memory, telling stories of pain and resistance. And commerce—tiny, informal, relentless—filled in the rest.

Today, Comuna 13 is a global pilgrimage site. Tourists pour in to walk its narrow alleys and ride its orange escalators, to hear local guides narrate the violence and resilience, to photograph graffiti that is as much documentation as decoration. What shocks me isn’t just the colour or energy—it’s how architecture and art here hold trauma without sterilizing it. A place once feared is now one of Medellín’s most visited neighbourhoods.

The architecture is not the polished kind. Clay brick stacked like improvisation, staircases turning into balconies, balconies into shops, shops into stages. It’s as though the hillside itself exhaled and produced a built organism. The escalators—those famous orange veins—slice through, not as luxury but as survival, dignity. Suddenly the city above and below connects. Suddenly commerce spills, murals climb, tourists wander, and locals claim their own narrative.

Standing there, I couldn’t help thinking: this is urban renewal without erasure. No starchitect glass icon, no sterile masterplan. Instead: infrastructure as catalyst, art as skin, community as architect. The graffiti doesn’t decorate—it dictates space. Every surface a manifesto, every turn a reminder that architecture is not just walls but permission to gather, to sell, to perform.

Comuna 13 feels like the anti-mall, yet it outperforms malls in every measure that matters. The density of encounter. The spontaneous collisions. The sensory layering: reggaeton thumping from one balcony, spray paint hissing from another, abuelas selling mango slices under the shadow of a mural of resistance.

It left me wondering: how many cities keep searching for renewal in corporate blueprints, while the true blueprint is right here—modest infrastructure + local will + the rough poetry of brick and paint.

Comuna 13 is not just Medellín’s best neighbourhood—it’s a reminder that the most radical architecture begins not with glass and steel, but with access, memory, and pulse.