On losing Frank Gehry, and remembering the decades he spent transforming material, space, and the future of architecture forever.

When I woke up today I didn’t plan to write an obituary, I’ve never written one before. I’m still processing the news that Frank Gehry has passed away. For those of us obsessed with the built world, it’s a strange feeling when someone who shaped your understanding of it leaves this world. So in respect to that feeling, I felt compelled to do my best.

In an industry increasingly seduced by glossy renderings, Pinterest-board aesthetics, and copy-paste floor plans, Frank Gehry insisted on the value of getting his hands dirty. On messy model-making. On the untidy sketch. Not because he wanted to “messy” looking structures, but because he believed that beauty in the modern era didn’t rely on classical ornament, beauty emerged from process, from the artistry of taking up space, the allure of exposing structure, and manipulating raw material with intention and honesty.

It also can’t be ignored that his success has, in many ways, obscured the real sensitivities of his work. “Starchitect” is a word people toss around easily, and I suspect Gehry was one of the reasons it exists at all. But reducing him to celebrity misses the deeper motivations. In addition to all the requirements of an architect, that is shelter, function, operations, maintenance and so on, Gehry truly thought like an artist, loved music like a musician, and built like someone trying to translate those emotions into form.

Moving through his buildings with that in mind translated my appreciation of his work more clearly than simply criticizing the underlining structure or use of surface material, and this became the lens that I appreciated his work through. Admittedly it was through the joyful appreciation of wonder, an area where professional criticism had to compete with spiritual nourishment. I go to Gehry’s buildings to hear the music and see the art.

In fact, in one Gehry enthusiasts opinion, his love for art and music didn’t just influence his work; it animated it. He drew inspiration not from completed masterpieces, but from the lived, chaotic lives of the artists themselves; the cluttered studios, unfinished thoughts, the sway between unwavering confidence and crippling self doubt, of the experiments that refused resolution. His buildings feel like jazz music, rock-and-roll, R&B leaping from high to higher, keeping time like a structural cadence before suddenly breaking free in a surprising burst of emotion. Unlike the repetitious structure of a greek temple or Miesian tower, he broke free from the mathematical grid and codified arrangement of form.

Witnessing a Gehry building for the first time, you feel all of this at once. Awe so immediate it actually hides how traditional his methodology was: windows proud of their walls, a clear celebration of entry, and the drama of level transition. Even the surface treatments of his most sculptural projects are often lifted directly from their surroundings. The novelty of his work blinds you to the classical training beneath.

Take 8 Spruce Street in New York: the façade ripples toward the river, merging tower and site in continuity. However on the city facing side the building becomes a standard skyscraper, only instead of one singular vertical form, he stacks the masses as if combining the skyline into one form. Or the University of Technology Sydney, whose tumbling brick-facing facade echo the historic Australian street it rises from. Even the massing is often a direct extension of context rarely fighting with its neighbours, but mirroring their effect. The boxy towers of L.A. sprouting out of the Disney Concert Hall, or the colourful metal planes intersecting like makeshift Costa Rican rooftops are just a few examples of this.

After all that’s said and done, what Gehry adds is movement. The tug of a street intersecting another street. A park pressing into the building’s side, shaping it like clay. Clouds dissolving into the sky like the transparent parts of his buildings dissolving with them. In all these cases, you can almost feel the neighbourhood sculpting the building, moulding it, informing him on what it wants to look and feel like.

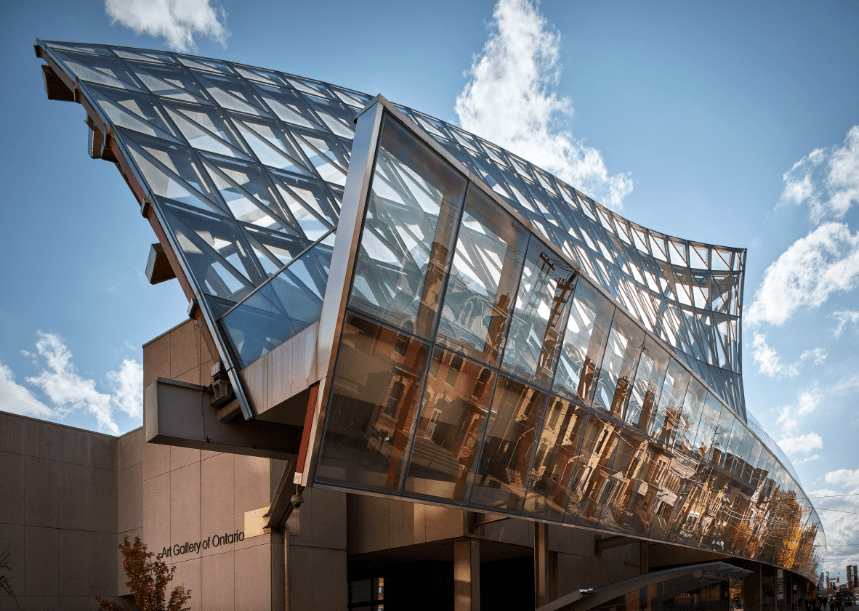

And nowhere is this more so than in in my home town of Toronto where I first met the work of Frank Gehry. While the Bilbao Guggenheim and the Fondation Louis Vuitton gather the spotlight, it’s in the code-restrictive, budget-conscious crucible of Toronto that Gehry performs a quieter miracle. The AGO renovation becomes a ribbon of wood threading through a dense city block, wrapped in curving glass, gleaming metal, and a path that affords you the time to wander.

You enter through a low-slung threshold, compression before expansion, a trick undoubtedly learned from Frank Lloyd Wright. The lobby and ticket area ripples with curved plywood to what is essentially under the soaring glass sail above. You trade your entry ticket and cross into the historic Grange courtyard. Above you, the AGO staircase unfolds like northern lights, curling, looping into itself, disappearing only to return again as it rises out of the now glass roof and into the sky-coloured metal addition above.

For me this room is a piece of magic. Like Fantasia. If you stripped the world of light and sound and poured all remaining energy into the massing of the building, I swear the movement you’d see is the same movement found in those wood floors, staircases, and wandering paths that meander their way around the porticos, zig-zigging against the boxy front, and spiralling up into the sky. Here, wayfinding becomes architecture; architecture becomes music, and music takes a sculptural form.

Let’s pause and consider for a moment what Gehry has done here. Drawing a direct line back over half a century ago, Kandinsky and others complained that Wright’s Guggenheim competed with the art it hosted, that the building he designed was too modern to showcase their work in. It felt as though Wright had taken the opportunity to set the drafting table aside, and adopt the hat of the artist himself. That argument persists today, and I don’t think its resolved here either, as Gehry’s own sculptural presence becomes one of the greatest artistic interventions in the building, and perhaps in the city as well.

Here however, Gehry makes the balance feel almost fluid, finding an equilibrium between gallery and exhibition. In his hands, the surrounding rooms tumble into one another like boxes nudged from a shelf, some poking through, some slipping down, some suspended from above. The experience is pure pleasure: intuitive paths, clear vistas, grand reveals and intimate moments, art held but rarely overshadowed.

Leaving the AGO is like waking from a dream. Everything made sense while you were inside, but it becomes more difficult to explain once you step back out onto the street. Looking back at the bowed glass façade reflecting an ordinary Toronto street made feels extraordinary: Victorian houses bending with the curve, streetcars scattering their red glow, passersby flickering across panes, all together activating the cadence of the soaring branchlike wood ribs that support them.

Architecture like this takes time. It isn’t instant. You can’t ignore it as it implores you to listen. You have to live with it, watch it age, shift, patina, adapt. Lady Morgan once wrote that “architecture is the printing press of the time and age it was erected in,” and that thought feels especially powerful now. Stepping back from my first encounter with his work at the AGO, I find myself thinking about the full arc of his buildings, where the world of Architecture was when he started with his small experimental home in Los Angeles, how it sculpted the industry to evolve with his distorted jewel box structures scattered across Europe, to the distinctly Canadian expression he carved into Toronto, not just with his building, but with the inspiration it afforded a young city becoming its own.

Together they form a record of a life spent reshaping the world of architecture, and it’s only now, in his absence, that the magnitude of that record fully settles in. Starchitect or more, we’ve now lost one of the greatest architects of all time, and what a privilege it was to live in the years Frank Gehry was shaping.