I arrived in Manchester on a cloudy afternoon, naturally. I stepped off the Metrolink at Piccadilly Gardens, dragging my backpack and carry on (both my partner and bag of hard drives and laptops), expecting the usual bustle of a city centre. What I didn’t expect was to look up and be struck by a building that felt like it had been airlifted out of a Soviet utopia and dropped squarely into the English skyline.

There it stood—patched with mismatched signage and ad hoc cladding, monolithic and unapologetic. Later that evening, in a burst of hotel-room Googling, I’d learn it once went by a different name: Piccadilly Plaza.

Piccadilly Plaza isn’t just a collection of buildings, it’s a complete architectural vision, fully cast in concrete. Rising from the heart of Manchester in the 1960s, this collection of modernist structures and forms was more than a commercial development. Envisioned as a self-contained urban district, and much like many great Modernist projects, it promised a new way of collecting and organizing civic life: offices, hotels, conference halls, restaurants, and retail, all into a unified piece of architecture.

It wasn’t just the height—though it still commands the skyline as one of Manchester’s tallest towers. It was the scale in every direction: a bold, unapologetic slab of concrete and glass that spans an entire city block, anchoring the Plaza with its sheer presence. Its form totally monumental and deliberate, unapologetic sculptural, aggressively modern, ideologically brutalist.

Brutalism is often misunderstood and seemingly only favoured nowadays by the ultra-nerdy architecture types (like myself). People associate it with dull grey apartment blocks, or the under-maintained urban projects in in nearly any city around the globe. But when you take the time, to really look at the ‘architecture’, that is the form, the structure, the gestalt, you see something else: romantic utopianism.

Piccadilly Plaza is a statement of aspiration. It occupies an entire city block with deliberate force, a megastructure of stacked uses, elevated walkways, cantilevered masses, and a matrix of mechanical support elements all worked into one complete plan.

The separation between base, podium, and tower is textbook modernism. You can feel its 1960s ambition reaching up embodying progress (albeit sampled quite obviously from the Soviets, and Frank Lloyd Wright too if you ask me), to give Manchester the kind of grand gesture that acknowledges the cities significant mark and position in history, both past and ongoing.

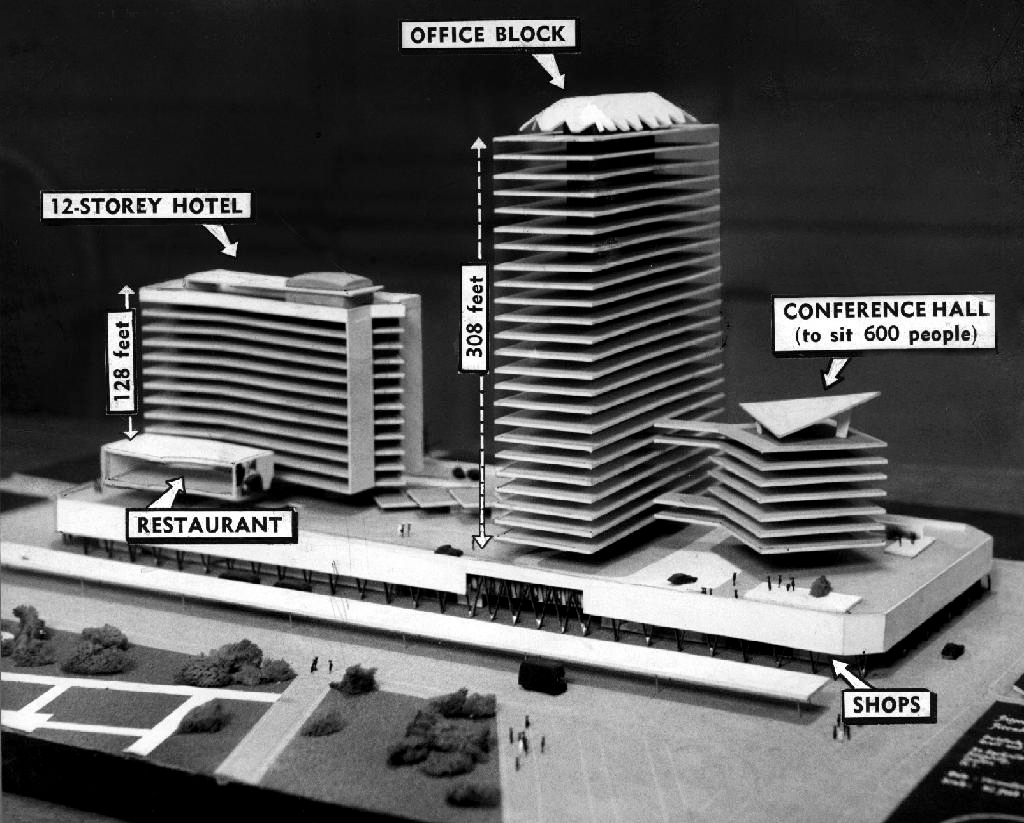

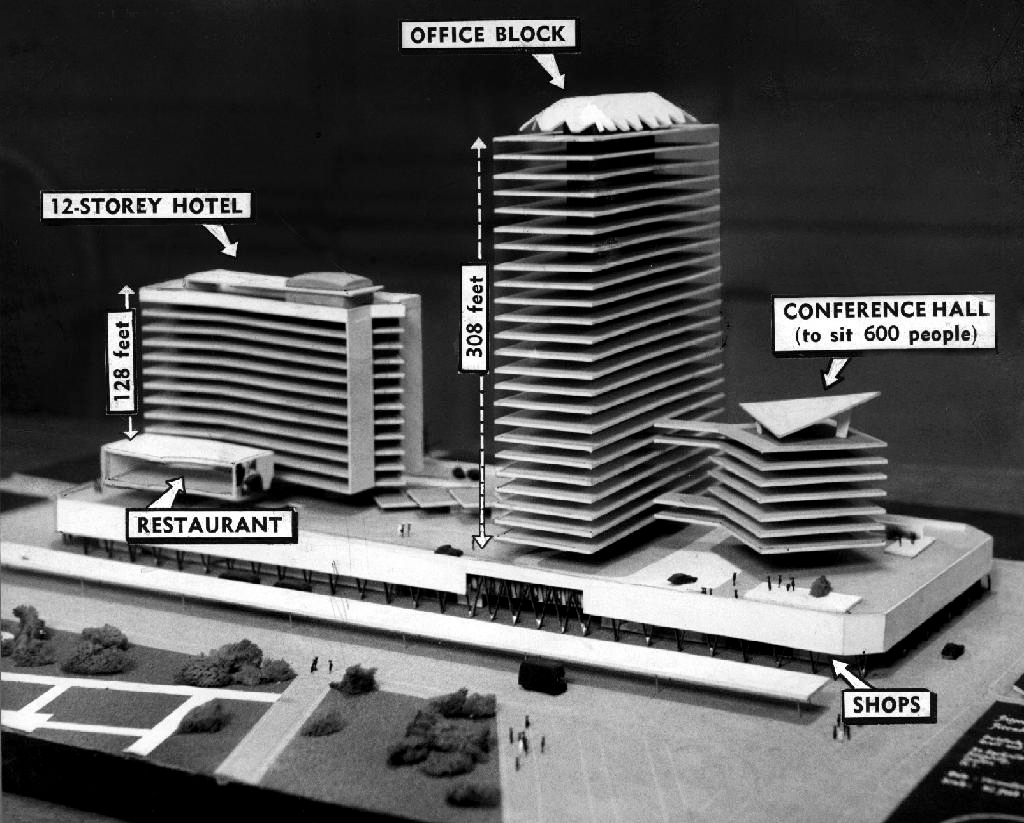

The 12-storey hotel floats above street level on massive pilotis, its slab-like form cutting horizontally across the site with absolute confidence. Beside it, the office tower rises with a kind of cool authority, anchoring the ensemble. At the plaza’s base, a wide platform of shops and concourses stretches along the street edge, lifted above the pavement like a stage. This was urbanism by architecture — the city reorganised through a modernist vocabulary of levels, volumes, and programs.

Every element was meant to serve a purpose: the hotel for business travellers, the conference centre as civic infrastructure, the retail podium as connective tissue. And yet, the result wasn’t just functional—it was visionary in its scale, a spatial diagram of how postwar Britain imagined the future: engineered, optimistic, and dramatically concrete.

Historical Dig: From my Hotel Room Curiosity to Architectural Archive

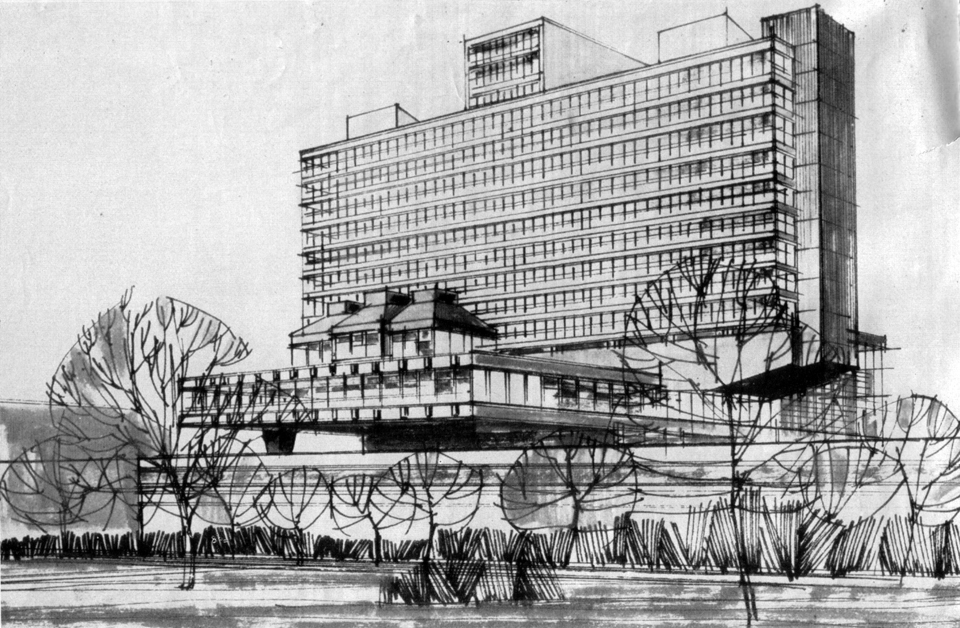

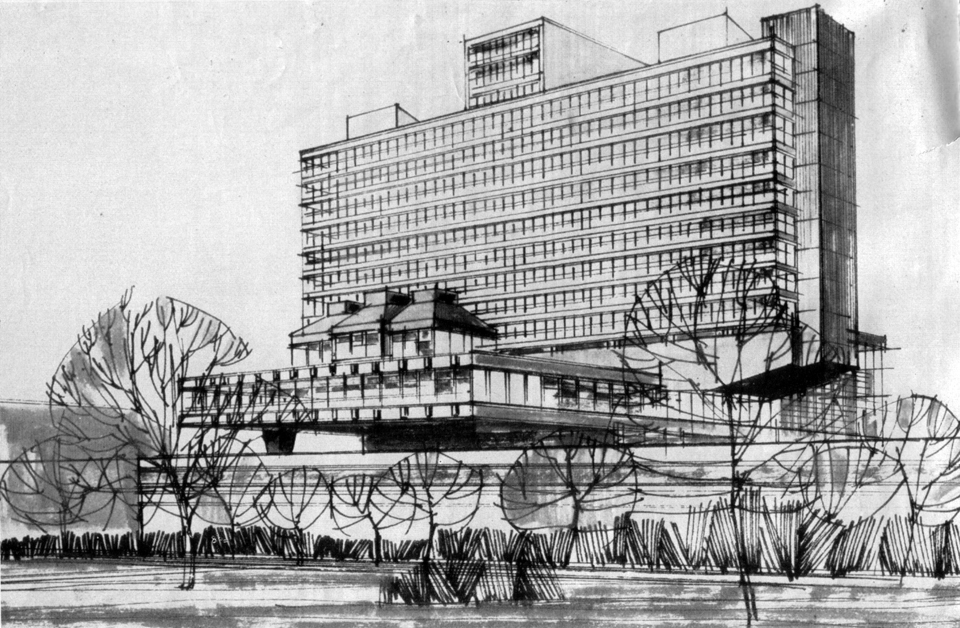

Back in my hotel, I did what any good nerd would do: I fell into a research hole. First stop: Sunley House. Designed by Covell, Matthews & Partners, built between 1959 and 1965, it was part of the larger Piccadilly Plaza scheme—a modernist reimagining of Manchester’s commercial core.

I found photos of the original architectural model, all sci-fi angles and optimistic scale figures. Drawings of the plaza’s grand vision, with annotations calling out to main zones (form truly follows function here). Grainy photographs from the 60s and 70’s showing the building taking life and the city operating around it.

And then: transformation. By the 2000s, it had been reclad, renamed, reimagined. Leslie Jones Architects added cladding with a kind of abstract circuit-board motif. A palimpsest of eras, layers of renovation, ownership changes, and cultural reappraisal.

At the rear of the complex, partially hidden, I found the spiraling ramp of the parking garage, a perfectly geometric coil of concrete that felt like something from a Corbusier sketchbook. Functional and sometimes all too common, but here it was sculptural too.

And then the windows, they don’t sit flush with the facade but project outward, essentially like capsules. From a distance, they break the mass of the tower into a kind of futuristic-mechanical rhythm—like space pods. Up close, they reveal their logic, once again in a Corbusier inspired aperture allowing more light in, creating a deeper reveal for shade, emphasizing the building’s depth and density.

Final Impressions from a Future That Was

What fascinated me more than any single building was how the entire Piccadilly Plaza was conceived as a total architectural composition. Each mass had a role to play. The 12-storey hotel, curved and horizontal, set up a conversation with the vertically dominant office block. The conference hall, with its dynamic, cantilevered planes, added a theatrical counterpoint, more like a civic sculpture than a hotel or mall complex. Even the low-slung restaurant and retail plinth pulled it all together with a Wrightian composition and rhythm. This wasn’t just a development, it was a city-scaled diagram of modern life, sculptured by use and expressed through form.

What endures in Piccadilly Plaza isn’t just concrete or geometry—it’s conviction. The entire project reads like a built creed of mid-century modernism: that architecture could shape behavior, organize civic life, and express the values of a rational, collective future. There’s something deeply moving about that—the way these buildings still carry the weight of their utopian ambitions, even as the city changes around them.

Decades later, we may look back with irony or critique. But standing beneath these forms, walking their shadowed podiums and ramps, you can still feel the clarity of purpose. A belief—not just in building—but in building better.