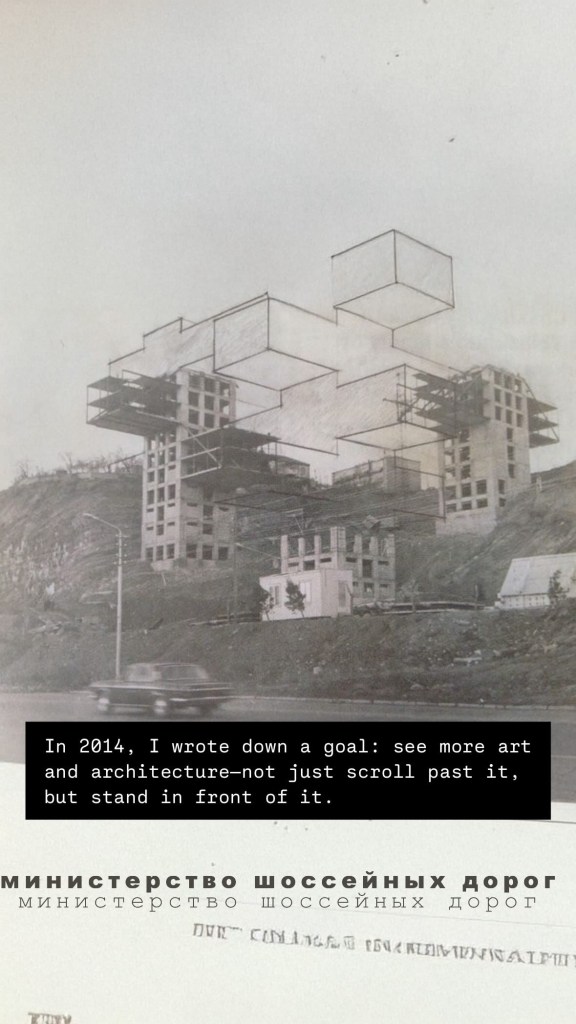

Tbilisi, Georgia – 1975

Architects: George Chakhava & Zurab Jalaghania

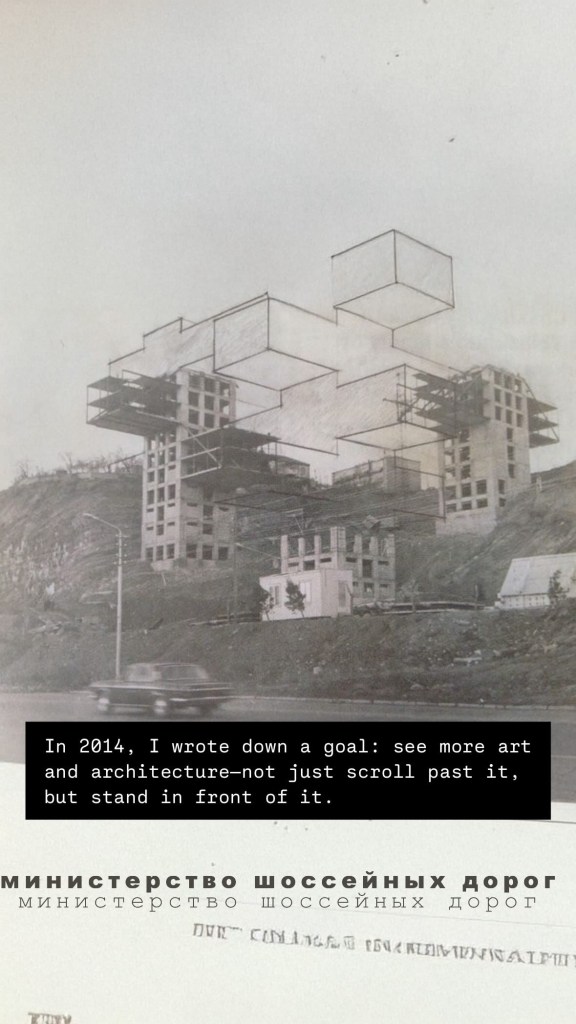

On my last day in Georgia, I made a small pilgrimage. Not to a church, but to a building. The Ministry of Highways, confidently rising on a forested slope at the edge of Tbilisi. It’s not downtown, not on a plaza, not trying to be seen by crowds, but deliberately away from the city accessible only by motorcar. That’s what immediately stood out to me: this was never meant to be urban spectacle. It was always meant to celebrate the automobile, yet remain in sync with nature — a vision that feels completely contradictory today, but made perfect sense in an era when Garden Cities, suburban expansion, and endless highways were imagined as a kind of utopia.

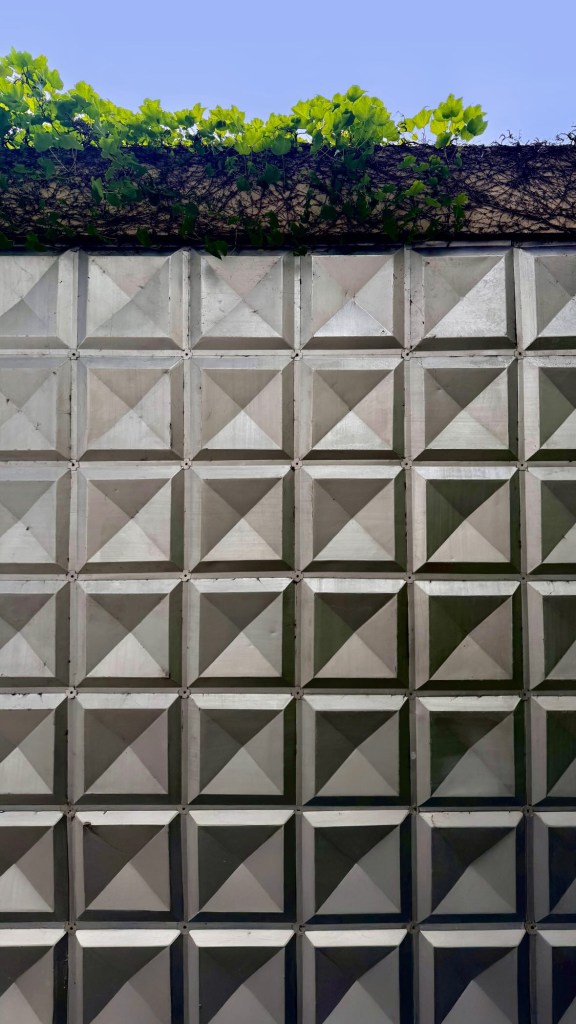

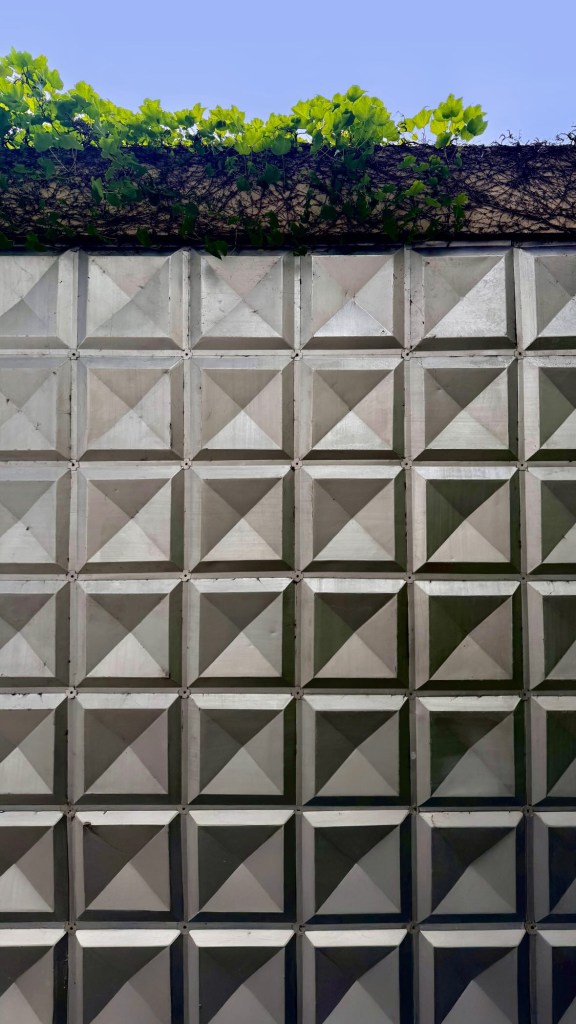

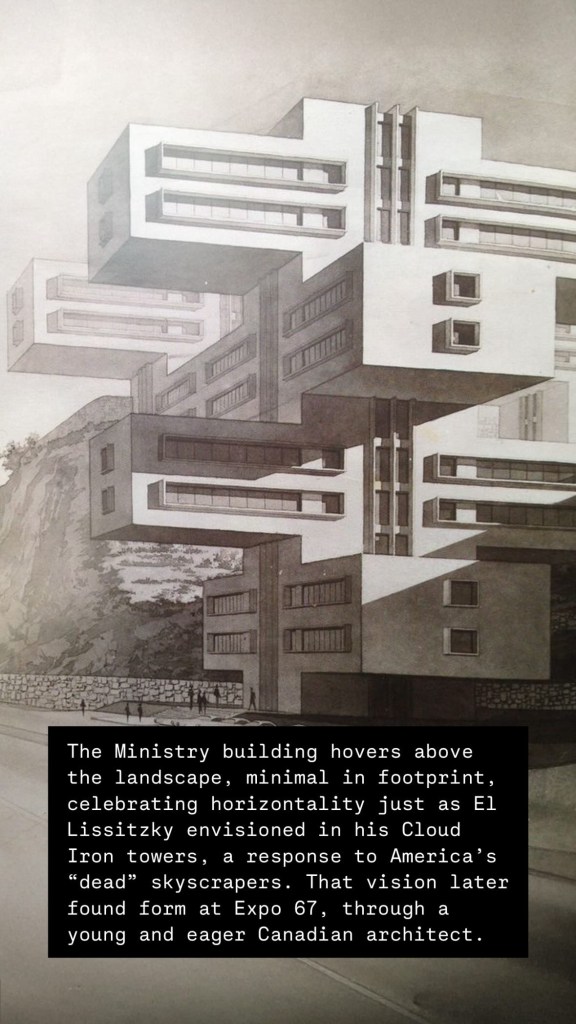

The building emerges suddenly from the trees as you drive around the bend. Five massive concrete slabs stacked and cantilevered like intersecting roadways, hovering just above a sprawling parking lot. It feels like it landed there. A kind of brutalist UFO with roots in both Soviet utopianism and deep architectural theory.

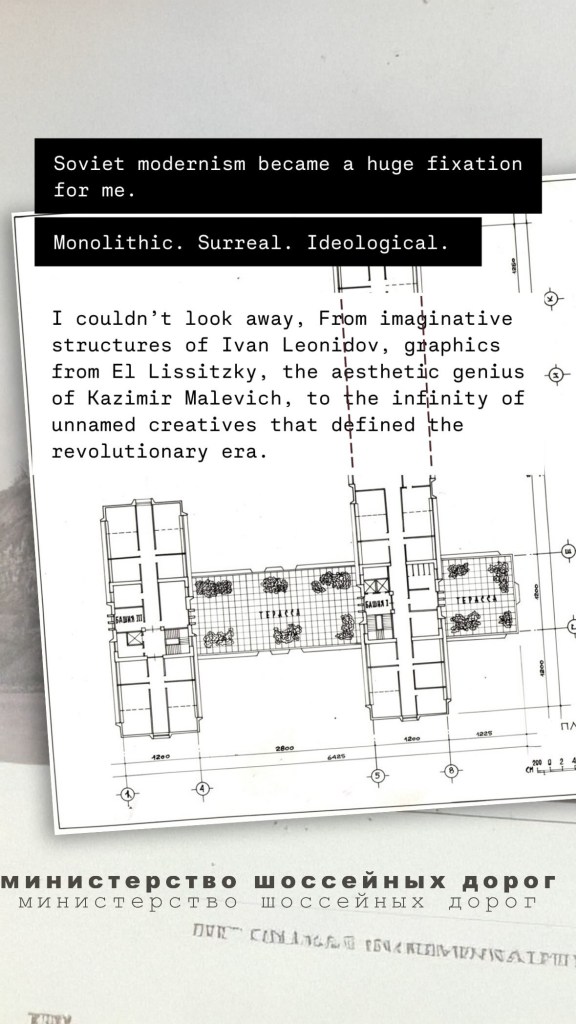

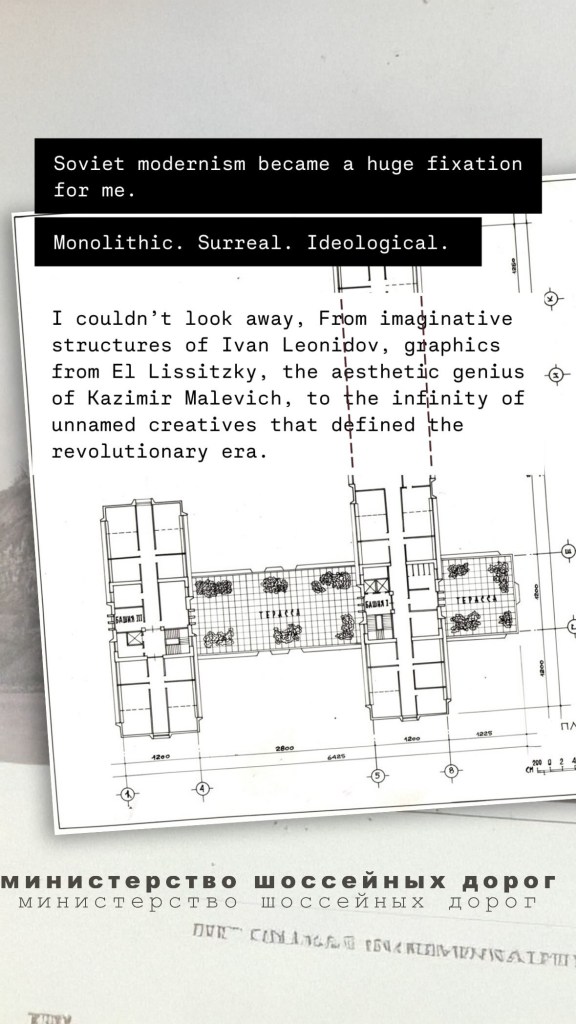

What continues to fascinate me is the ideological ambition embedded in this form. It wasn’t just about aesthetics, it was about a different vision of how people live and work. In contrast to the American skyscraper’s verticality, Soviet theorists like El Lissitzky imagined “cloud iron” towers: horizontal, interconnected forms elevated above the ground to preserve nature and reduce alienation. This building takes that radical idea and makes it real.

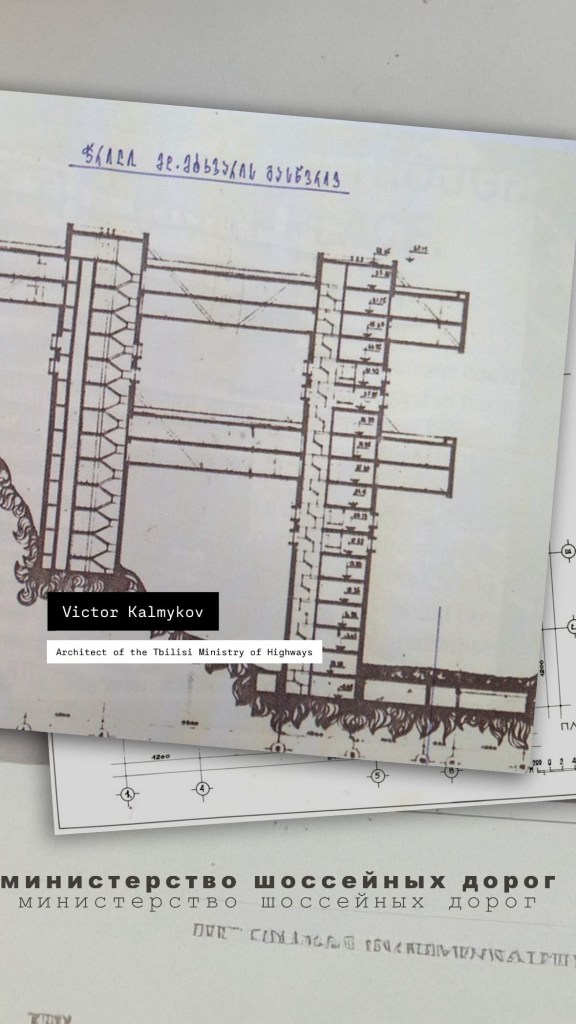

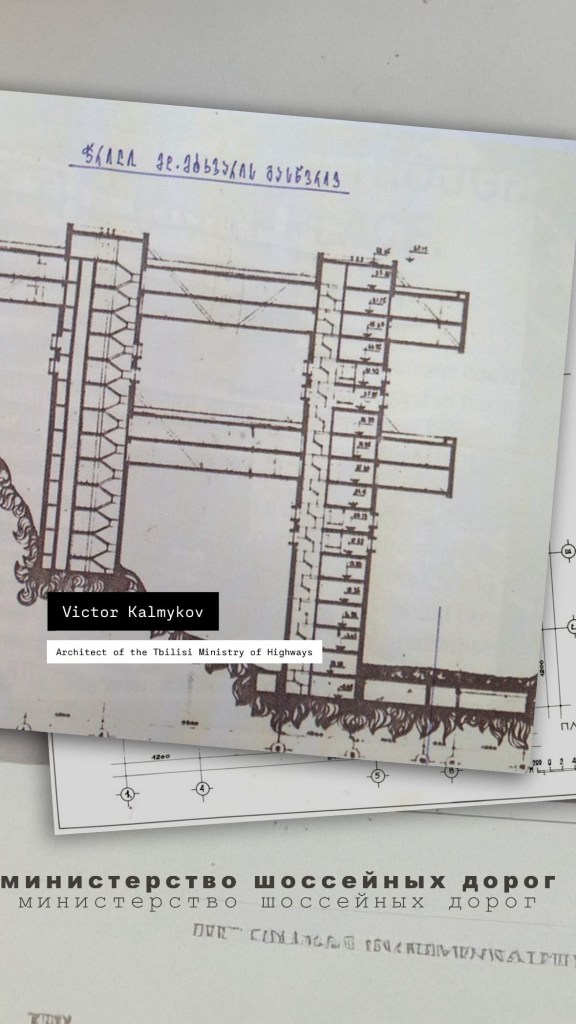

Chakhava, the architect (and then-minister of highways), used his position to bypass the bureaucracy and get it built, one of those rare moments where vision and authority aligned. The result is something totally singular, yet part of a broader moment in architectural experimentation.

It also reminds me of Moshe Safdie’s Habitat 67, another radical structure from the same era. Though very different in context, both projects share a resistance to monolithic verticality. They’re fragmented, modular, human-scaled in their own alien way. Buildings that want to touch the ground, not dominate it.

And I can’t help but wonder: what did the Japanese Metabolists or the British experimental collective Archigram make of this building — if they saw it at all? The Ministry feels like it could have stepped out of one of their sketchbooks or collages: infrastructural, spatially ambitious, and deeply in tune with the landscape. Maybe it was a case of parallel thinking, ideas blooming independently across continents, shaped by a shared optimism about architecture’s potential to reshape life.

That lineage doesn’t end there. Decades later, architects like Will Alsop would carry those ideas forward, not as theory, but as built form. His Sharp Centre for Design in Toronto, with its bold tabletop hovering on tilted stilts, channels that same defiance of gravity and convention. It takes the modularity and elevated logic of Archigram and the Ministry, and infuses it with colour, wit, and a distinctly public spirit. Where Chakhava floated infrastructure above nature, and Archigram envisioned cities in motion, Alsop gave these radical gestures a place in the everyday city. It’s a throughline of architecture as both infrastructure and fantasy, unapologetically expressive, but grounded in the real.

Standing beneath the stacked slabs of the Ministry, surrounded by trees and highway noise, it felt like architecture caught in a rare act of idealism. Not nostalgic, not naive, just radical.

Architects: George Chakhava & Zurab Jalaghania

Architects: George Chakhava & Zurab Jalaghania

Architects: George Chakhava & Zurab Jalaghania

Architects: George Chakhava & Zurab Jalaghania

Architects: George Chakhava & Zurab Jalaghania

Architects: George Chakhava & Zurab Jalaghania

Architects: George Chakhava & Zurab Jalaghania

Architects: George Chakhava & Zurab Jalaghania

Architects: George Chakhava & Zurab Jalaghania

Architects: George Chakhava & Zurab Jalaghania