From Venice to Toronto: The Inspiration Behind Harbour City

Since its founding, Toronto has been grappling with what to do with its sprawling fresh water lakefront, and its identity as a Global City. The waterfront of Toronto has long been a source of both inspiration and frustration for urban planners and residents alike. From the early days of the city’s founding, the vast expanse of Lake Ontario has represented both an opportunity for growth and development, as well as a daunting challenge in terms of how best to utilize and connect with this valuable and cultural resource.

This sentiment is not new, as the waterfront of Toronto has been a meeting place for Indigenous peoples well before Europeans arrived. Serving as a hub for trade, transportation and community for centuries, the natural harbour formed by sediment blown from Scarborough Bluffs created a protective harbour, cradled by both the Don and Humber Rivers providing ample routes to this formidable meeting place.

With this long and varied history, culminating with the cities formal founding as the town of York in 1793. The late 19th century saw a boom in industrialization and trade, and by the 1970s, Toronto was competing with Montréal to become the leading Canadian city. The 1990s brought a wave of condo development, and the city continued to grow and evolve in the 2000s as a globalized metropolis. More recently, Sidewalk Labs proposed a tech-driven urban utopia.

1793 – The Founding of the Town of York

1889 – Industrial Revolution hits Toronto

1970’s – Competing with Montréal

1990’s – Condo-fication of Downtown

2010 – Sidewalk Labs, AirBNB, & Drake.

2020 – Covid-19 Lockdowns Toronto

In the 1970s, two ambitious projects were proposed that aimed to revolutionize the waterfront and bring new life to the city: Harbour City and Ontario Place. Although one was ultimately abandoned and the other met with mixed success, the story of these projects offers a fascinating glimpse into the possibilities and pitfalls of waterfront development, and the enduring struggle to create a meaningful connection between Toronto and its lakefront.

Brief overview of Harbour City and Ontario Place

Harbour City was a master plan for a new waterfront community in Toronto, designed by Canadian architect Eberhard Zeidler and proposed in the late 1960s. The plan called for the relocation of the city’s island airport and the use of the reclaimed land to create a series of canals and bays, reminiscent of Venice or Amsterdam. The vision for Harbour City included low-rise, mixed-use buildings, a separation of pedestrian and vehicular traffic, and an emphasis on public transit and density. The project was also intended to be fully integrated with public transit and to have a view of the water for everyone, regardless of their economic status.

Ontario Place, on the other hand, was a theme park that opened in 1971, also designed by Eberhard Zeidler. It was built on artificial islands in Lake Ontario, east of downtown Toronto. The park featured a number of unique architectural elements, including a series of interconnected “pods” suspended above the water and a large, geodesic dome. It was intended to showcase the province’s industrial and agricultural prowess, as well as to provide a variety of entertainment and recreational options for visitors.

Comparison to other waterfront development projects such as Dubai’s “floating cities” and Venice

Dubai’s “floating cities” are a prime example of ambitious waterfront development projects that have faced criticism. The Palm Jumeirah and The World islands, built in the 2000s, are man-made islands in the shape of a palm tree and the world map respectively, intended to be luxury residential and tourist destinations. However, they have been criticized for being environmentally and financially unsustainable, as well as not being regionally appropriate, and ultimately a failure in terms of livability.

Similarly, Venice, with its maze of canals, bridges, and historic buildings, is a unique and popular tourist destination, but it also faces major challenges such as overcrowding, rising sea levels, and erosion. Both Dubai and Venice have faced criticism for the negative impact of tourism on the environment and local communities.

On the other hand, Harbour City, designed by Canadian architect Eberhard Zeidler and consulted by Jane Jacobs, was intended to be a livable and sustainable waterfront community that would have included everyone, regardless of their economic status, and would have had a positive impact on the environment, by using public transit and separating pedestrian and vehicular traffic. Similarly, Ontario Place was designed to showcase the province’s industrial and agricultural prowess and to provide a variety of entertainment and recreational options for visitors, in a sustainable and unique way.

Toronto’s historical relationship with its lakefront and the challenges in developing it.

Toronto’s historical relationship with its lakefront has been marked by a tension between the desire to make the most of this valuable resource, and the challenges of doing so. From the earliest days of the city’s founding, the lakefront has represented both an opportunity for growth and development, as well as a daunting obstacle in terms of how best to utilize and connect with it. This challenge was further exacerbated by the fact that much of the lakefront was taken up by heavy industry, making it an uninviting and inaccessible place for residents and visitors alike.

Over the years, various plans and proposals have been put forward to try to address these issues and revitalize the waterfront, but many have faced significant obstacles in terms of funding, political support, and community opposition. Harbour City and Ontario Place were among the most ambitious and high-profile of these efforts, and although they ultimately took very different paths, both attempted to tackle the waterfront development challenge in their own unique way.

II. The Design of Harbour City

The design of Harbour City was heavily influenced by the architectural zeitgeist of the 1960s and 1970s, which saw a renewed interest in modernism and futuristic design. The master plan, created by Canadian architect Eberhard Zeidler and consulted by Jane Jacobs, Hans Blumenfeld and others, proposed a low-rise, mixed-use development that would be connected to the rest of Toronto via a ring road, with public transit, canals, and an assortment of modular buildings short on height, varied in use, and high in density. The design also separated pedestrian and vehicular traffic, with buildings planned to straddle the street.

This embrace of modernism and futuristic design was evident in other notable architectural projects in Toronto of that time, such as the new City Hall, designed by Finnish architect Viljo Revell, the Eaton Centre, designed by Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava, and the CN Tower, designed by Canadian engineer John Andrews, all of which were built in the 60s and 70s. All of these buildings showcase the futuristic design of the era, and is a testament to the city’s embrace of modern architecture, and its willingness to take bold steps in planning for the future.

The master plan and architectural design

The master plan for Harbour City, commissioned by the provincial government of Ontario and designed by Canadian architect Eberhard Zeidler and his architectural firm Craig, Zeidler & Strong, proposed a waterfront community of 60,000 residents on a man-made island adjacent to Ontario Place. The island was to be created by relocating the city’s island airport and filling in parts of the lake to form a series of canals and bays, creating a water city similar to Venice or Amsterdam.

The development was intended to be a low-rise, horizontal groundscraper, with buildings no taller than 10 stories. The residential areas were designed to be single-family, low-rise and mixed-use, and the commercial areas were designed to be mixed-use, with shops, restaurants, and other amenities. A terrace level was intended to conceal the car movement. The plan also included a ring road to connect the community to the city proper, and a public transit system to connect residents to the rest of the city.

The architectural design of Harbour City was heavily influenced by the modernist and futuristic design of the era, and incorporated clean lines, geometric shapes, and an emphasis on functionality and efficiency. The buildings were designed to be modular, with a variety of different footprints and uses, and the emphasis was on creating a dense and walkable community. The development also included a canal system that would provide every resident with a view of the water. The architects, consultants, and the province of Ontario worked together to create a plan that will be inclusive to all, regardless of economic status, and environmentally friendly, in order to create a sustainable and livable waterfront community.

Jane Jacobs and her consulting role on the project

The master plan for Harbour City was developed in consultation with renowned urban thinker Jane Jacobs, who had recently moved to Toronto in 1968. Jacobs was known for her influential book, “The Death and Life of Great American Cities,” in which she advocated for mixed-use, walkable communities and the importance of a diversity of people and uses in urban neighbourhoods.

As a consultant on the Harbour City project, Jacobs had the opportunity to put her theories into practice and help shape the development into a model of sustainable urbanism. She was excited about the project and even appeared in a promotional film for Harbour City in 1970, where she proclaimed, “It may well be the most important advance in city planning that’s been made this century.” In the film, she even pointed out the exact building she wanted to live in.

Jacobs’ input on the project helped to ensure that the development would be inclusive and accessible to all, with an emphasis on affordability and walkable streets. She also helped to advocate for the separation of pedestrian and vehicular traffic and the integration of public transit. Her vision for the project would have been a “liveable” and “emotionally rich” community where people of all backgrounds could live, work and play.

Comparison to Habitat ’67 in Montreal

The design of Harbour City, with its emphasis on low-rise, modular buildings and a network of canals, has some similarities to the architectural design of Habitat ’67 in Montreal. Habitat ’67, designed by Canadian architect Moshe Safdie, was a housing complex built for the 1967 World Exposition. It was also an experimental housing project that aimed to create a new kind of urban living, with a mix of private and public spaces, and a focus on creating a sense of community.

Like Harbour City, Habitat ’67 was designed to be a low-rise, mixed-use development, with residential units stacked on top of each other in a modular fashion. Both developments also incorporated a network of open spaces and water elements, with Habitat ’67 featuring a series of interconnected terraces and Harbour City featuring a system of canals. Both developments were also designed to be inclusive and accessible, with a mix of affordable and market-rate housing.

However, there are also some key differences between the two developments. Habitat ’67 was built for a specific event and was intended to be a temporary housing solution, whereas Harbour City was planned as a permanent development. Habitat ’67 also had a more sculptural, organic form, whereas Harbour City had a more geometric, modernist aesthetic. But overall, both developments were a reflection of their time and a vision for new forms of urban living, and it is interesting to see the similarities and differences between the two projects.

III. The Failure of Harbour City

Despite having the support of the province of Ontario and urban thinker Jane Jacobs, Harbour City was ultimately never built. The project faced several challenges, including public opposition to the proposed Spadina Expressway and concerns about the environmental impact of filling in parts of the lake to create the development.

Many opponents feared that Harbour City would bring the proposed expressway closer to reality, stretching into downtown and connecting with the Gardiner Expressway that still runs along Toronto’s waterfront today. There were also concerns about the impact of filling in parts of the lake on the environment and the potential for pollution.

The failure of Harbour City reflects the historical challenges of developing Toronto’s lakefront. From the city’s founding, the region has grappled with how to best use and develop its sprawling lakefront. The waterfront has long been seen as a valuable asset, but its development has been hindered by competing interests and challenges, including concerns about the environment, accessibility, and the need to balance development with preservation.

In recent years, there have been renewed efforts to develop the waterfront, with initiatives such as the Sidewalk Labs’ project, which has proposed a bold vision for a mixed-use, sustainable neighbourhood on the waterfront. However, the challenges of developing the waterfront remain, and the failure of Harbour City serves as a reminder of the difficulties of balancing competing interests and creating a truly inclusive and sustainable development that reflects the needs and desires of the community

- Reasons for the project’s cancellation, including public opposition to the Spadina Expressway and concerns about environmental impact

- Impact on Toronto’s waterfront development

- Mention of how the failure of Harbour City reflects the historical challenges of developing Toronto’s lakefront

IV. The Success of Ontario Place

Despite the failure of Harbour City, the province of Ontario was able to successfully open Ontario Place in 1971, just one year after the failure of Harbour City. The development was designed to be a showcase of the province’s prowess as an industrial and agricultural leader, highlighting its history, geography and future potential. The park featured a variety of attractions, including a five-pod pavilion, the world’s first IMAX theatre, an open-air forum and a marina, that provided a wide range of options for visitors.

The design of Ontario Place is considered a masterpiece of futuristic and space age architecture, the geodesic dome and the pods still look modern and unique even 70 years later. This is a testament to the architect Eberhard Zeidler’s vision, who was able to create a unique and exciting place that attracted thousands of visitors every year.

Ontario Place was a direct response to the success of Montreal’s Expo 67, which was held on a man-made island and attracted millions of visitors. The province of Ontario was keen to compete with Quebec and Montreal in terms of tourism, and Ontario Place was seen as a way to do this. The success of Ontario Place was due in part to the province’s embrace of modernism and futuristic design, which was reflected in other iconic buildings in the city such as the new city hall and the Eatons centre.

Ontario Place was a great success and was a popular destination for many years, it’s a shame that the park was closed down in 2012 due to lack of funds, however, the memories and the architectural legacy of the park still remains today.

The design and construction of the pods and geodesic dome

The design of Ontario Place’s five pods and geodesic dome was a major architectural achievement. The pods were designed to be lightweight and modular, with each one housing a different attraction or activity. The geodesic dome, which was the largest of its kind at the time, was used as an IMAX theatre and was considered a marvel of engineering.

The pods were constructed using a combination of steel and aluminum, and were suspended above the water on steel pilings. Each pod was shaped like a triangular prism and was connected to the others by a series of walkways and bridges. The geodesic dome was made of a steel framework and covered in a Teflon-coated fiberglass fabric.

The construction of the pods and dome was a challenging and complex process, as they had to be built on the water and withstand the harsh conditions of Lake Ontario. The engineers and architects had to take into account the wind, waves, and ice, as well as the possible effects of boat traffic and the weight of the visitors. The pods and dome were also designed to be easily accessible by the public, with ramps and elevators leading to the upper levels.

The combination of the unique design, the engineering and the construction of the pods and dome make Ontario Place a truly unique and iconic place, it’s a monument to the architectural and engineering skills of Eberhard Zeidler and his team, and it remains a legacy of the province’s vision and ambition to create a world-class waterfront destination.

Comparison to other iconic buildings and structures around the world

The design of Ontario Place’s pods and geodesic dome can be compared to other iconic buildings and structures built around the same era, such as the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, designed by Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers, and the Lloyd’s building in London, designed by Richard Rogers. Both of these structures feature bold, futuristic designs that incorporate the use of exposed mechanical systems and other innovative architectural elements.

Another example is the Capsule Hotel in Tokyo, designed by Kisho Kurokawa, which was built in 1979, is a prime example of the Metabolist architectural movement. The hotel is composed of small, modular units that can be stacked to create a variety of different configurations.

In more recent years, the concept of modular, prefabricated structures has been adopted by several high-profile architecture firms and projects, such as the Bjarke Ingels Group’s proposal for a modular housing development in New York City, and the work of Japanese architect Shigeru Ban, who has designed several emergency housing projects using modular, reusable elements.

In conclusion, the design of Ontario Place’s pods and geodesic dome is a unique and iconic structure that was ahead of its time in terms of its innovative design, construction and engineering. Its legacy continues to inspire architects and designers around the world to push the boundaries of what is possible with modular, prefabricated structures.

V. Conclusion

- Summary of the potential benefits and drawbacks of large-scale waterfront development projects such as Harbour City and Ontario Place

- Reflection on the uniqueness and architectural significance of the pods and geodesic dome at Ontario Place

- Perspective on the ongoing efforts to develop and revitalize Toronto’s lakefront and how the lessons learned from Harbour City and Ontario Place can be applied.

In conclusion, large-scale waterfront development projects such as Harbour City and Ontario Place have the potential to bring economic, social and cultural benefits to a city, but also come with certain drawbacks. The design and construction of Harbour City, and its consultation with urban thinker Jane Jacobs, represented a new approach to urban planning that incorporated principles of density, mixed-use, and public transit integration. However, the project was ultimately cancelled due to public opposition to the Spadina Expressway and concerns about environmental impact.

Ontario Place, on the other hand, was a successful project that brought an innovative and futuristic design to the waterfront. Its iconic pods and geodesic dome continue to be an architectural marvel and a popular tourist attraction. However, in recent years, the park has seen a decline in attendance, and efforts to revitalize the area are ongoing.

The ongoing efforts to develop and revitalize Toronto’s lakefront, such as Sidewalk Labs, serve as a reminder of the challenges and opportunities that come with large-scale waterfront development projects. Toronto’s position as a global architecture destination for imagination and creativity is undeniable, as seen in the many other iconic buildings and structures in the city, from the CN Tower to the AGO, the ROM and the Royal York Hotel. The lessons learned from Harbour City and Ontario Place can be applied to future waterfront development projects to create sustainable, livable, and unique spaces for residents and visitors alike.

As Toronto continues to grow and evolve, it is important to remember the lessons learned from the Harbour City and Ontario Place projects. While these ambitious endeavours ultimately fell short, they served as a testament to the city’s potential for imagination and creativity in design and architecture. It is crucial that we continue to strive for bold and innovative ideas in the development of our waterfront and city as a whole. With a rich history of design excellence, from the Royal York Hotel to the CN Tower, Toronto has the potential to re-establish itself as a global leader in architecture and urban planning. Let us continue to push the boundaries and think outside the box, creating a city that is not only livable and functional, but also a source of inspiration and wonder for generations to come.

Harbour City is an idea for a new kind of urban community built around water on a location west of Toronto Islands. With re-development of the Island Airport, it would eventually house some 45,000 – 50,000 people. Prepared by the Ontario Government, the concept for Harbour City could begin the re-development of Toronto’s lakefront to make it one of the most exciting waterfronts in the world.

Original Toronto Star caption: Trade and Development Minister Stanley Randall unveiled on Wednesday the Ontario government’s proposed, $500 million Harbor City, a waterfront mini-city of tree-lined streets and clear lagoons. Harbor City is one of several new waterfront projects.

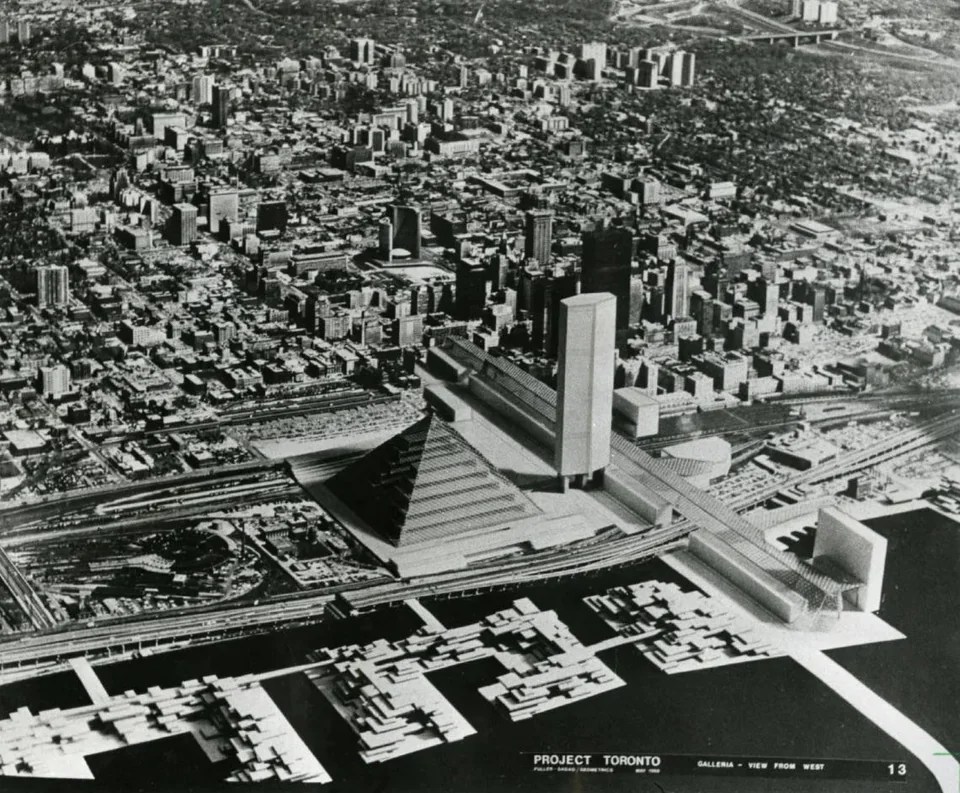

Project Toronto’ by Buckminster Fuller, 1968 – A redesign of Toronto’s waterfront, featuring an over-the-water miniature city, giant pyramid, and more

Project Toronto

Proposed: 1968

Fizzled: 1968

Why it wasn’t meant to be: Buckminster Fuller’s plan to build a waterfront university that would feature a 20-storey pyramid and “Pro-To-Cities” built in the inner harbour, would have profoundly changed this city’s downtown core. With plans for Metro Centre arising at the same time, however, Project Toronto never really went anywhere.